Germany has so much to teach the world about music education.

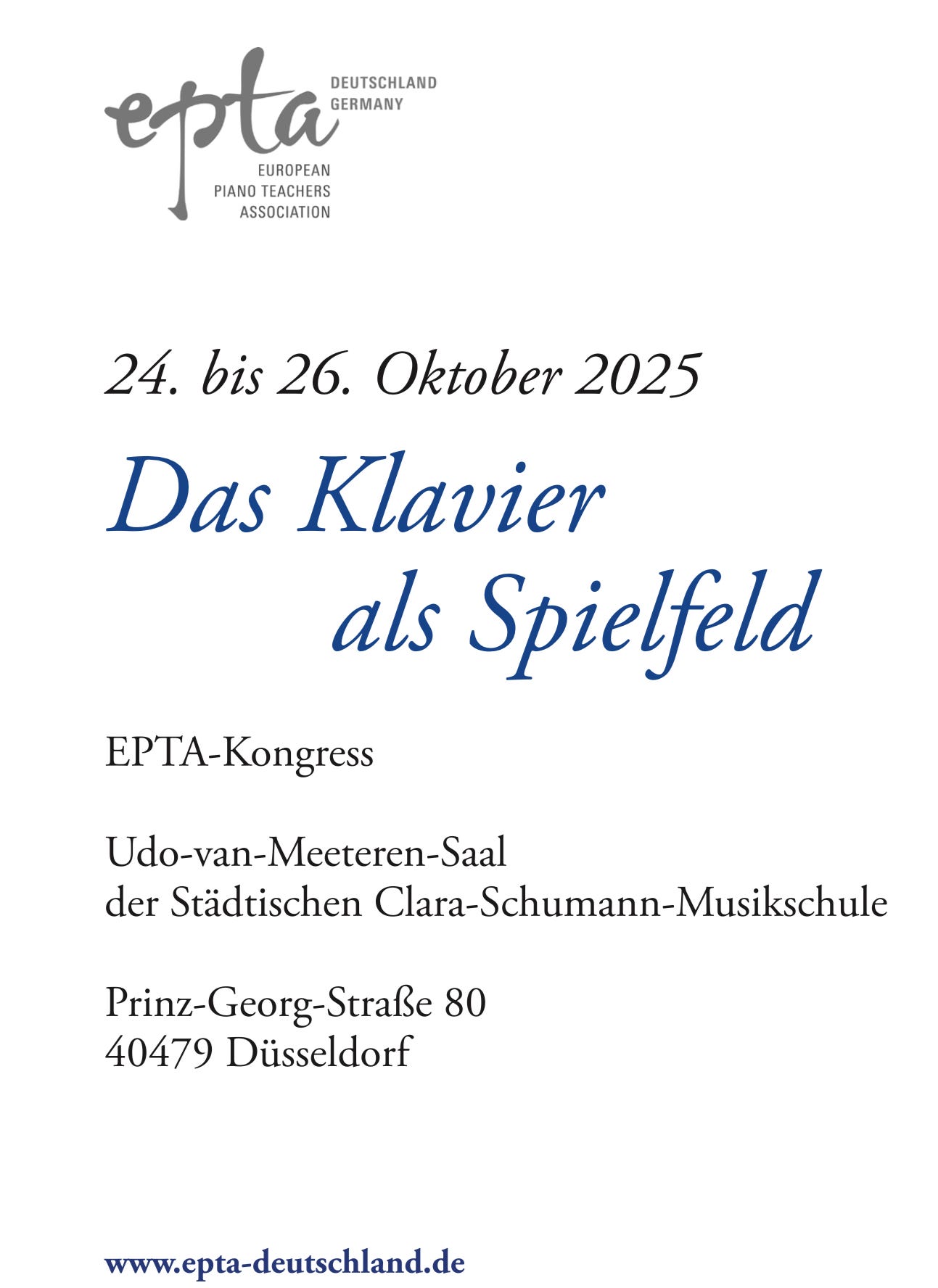

I’ve just attended the autumn conference of the German wing of the European Piano Teachers’ Association (EPTA) and I come away feeling inspired and excited and—perhaps best of all—welcome. What a lovely experience it was!

Below are a few highlights from the conference, which will appeal to anyone interested in teaching piano creatively.

Briefly though, before I begin: the more I explore German music pedagogy, the more struck I am by its insight and its effectiveness. Although my mother tongue English has many more speakers, there’s a richness and a profundity to German educational approaches that belies its relatively small population of speakers (which of course includes more than just the population of Germany, e.g.the Austrians and some of the Swiss).

Perhaps this is unsurprising given its cultural history and the liveliness of its contemporary musical landscape, but what strikes me is that so little of this pedagogical treasure makes its way to the English-speaking world! It seems a tremendous wasted opportunity, particularly when so many of my German colleagues speak English so fluently.

Without further ado, on with the post…

The Piano As Playground

At the heart of the conference was the gentle reminder: we play the piano.

That message lay at the heart of Josephine Mücksch-Karpp’s opening talk, which included a lovely line from Stefan Zweig’s novel about chess, the Schachnovelle:

„Ich spiele Schach im wahrsten Sinne des Wortes, während die andern, die wirklichen Schachspieler, Schach ernsten.“

This line translates roughly as “I play chess in the true sense of the word, whereas the others, the real chess players, are ‘seriousing’ chess”.

Playfully using the word “serious” as a verb to make a serious point is masterful use of language.

How many of us spend too much time ‘seriousing’ the piano?

Playing the whole piano

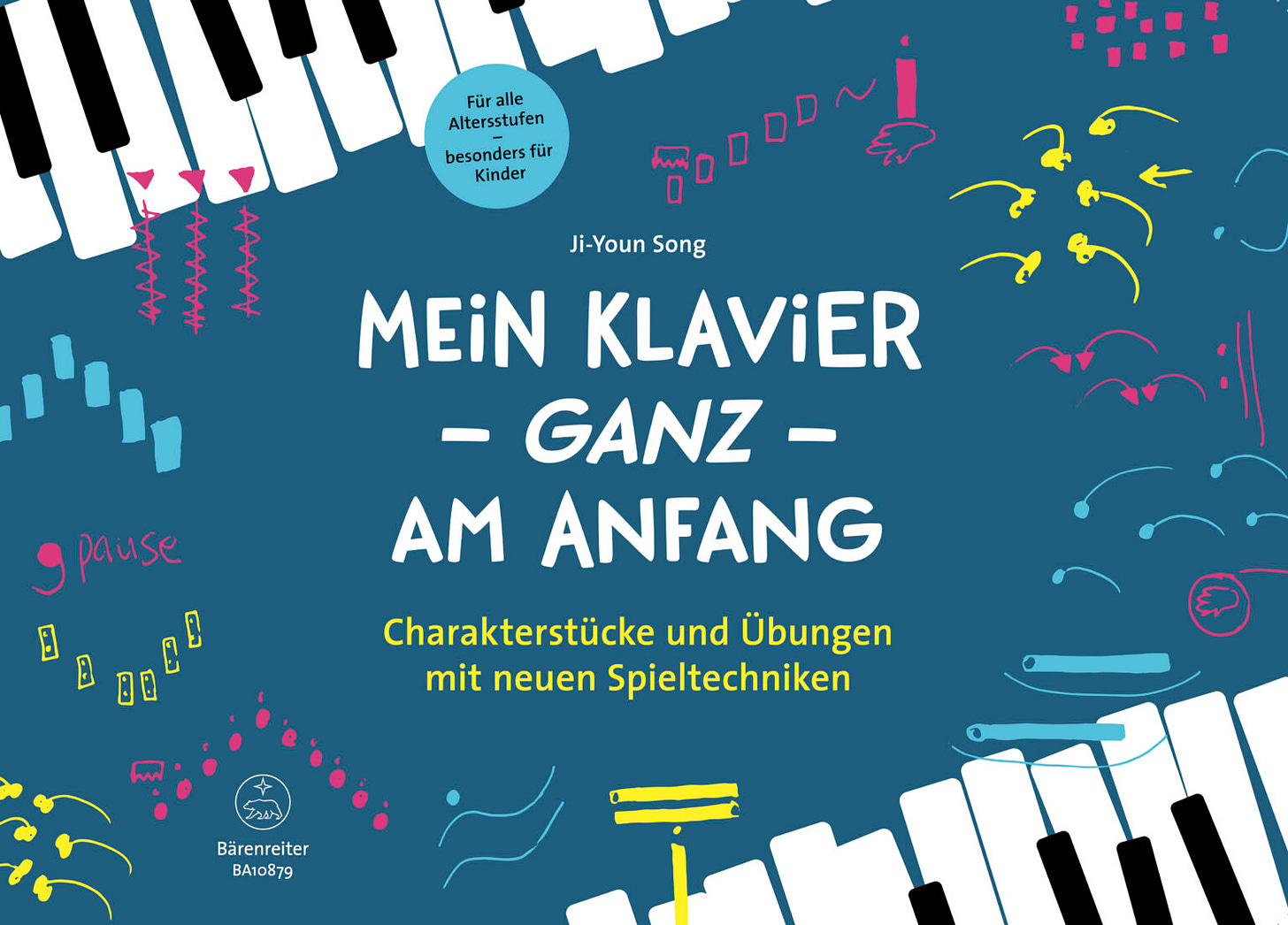

Ji-Youn Song’s new piano method, Mein Klavier — GANZ — am Anfang, is the most exciting new piano method I have encountered in years. Published by Bärenreiter, this unique set of books cries out for an English translation.

I’ve bought them and I’m planning on trying them out with one of my beginners very soon. (It’s all the more remarkable that I should be doing this this because I emphatically am not a fan of Experimental Music, which is what this method introduces!)

What’s so great about these books? Simple: they are great fun, and a really powerful way to get kids excited about acoustic pianos.

One book (the Lehrerheft) is a series of nine lesson plans that introduce beginners to a variety of playing techniques within and on grand and upright pianos. These lesson plans are designed to make up the first lessons the child ever takes and will fill them with wonder and excitement about the instrument before they begin working through your normal method books.

As they work through the lessons, the kids explore the piano through structured games, creating their own graphic notation and their own compositions. A second book (the Spielheft) is a set of outlines for semi-improvised pieces and exercises.

I will likely write more about these books in the coming months — watch this space.

There was also a wonderful presentation by Corrina Weller on a closely related topic: using Nicolaus A. Huber’s Ton-Geschenke as an introduction to similar experimental techniques. This is part of the first movement of Pour les Enfants du Paradis, published by Breitkopf & Härtel. Corrina and two students brought the pieces to life in a very entertaining way — clearly it’s something that kids really engage in.

Gamification

Klaus Kauker’s excellent talk about the use of the theory and practise of gamification offered a wide variety of perspectives on how a) most piano teachers already use gamification in their teaching and b) the potential benefits of including more. He drew our attention to Yu-Kai Chou’s Octalysis Framework, which maps out how gamification can be highly motivating…

…and showed us how we are already working to help our students develop many of these things, including a sense of ownership, accomplishment, empowerment and even epic meaning. He gave several interesting ideas for how we could take this further, drawing on insights gleaned from this fascinating article (amongst other places) and was refreshingly balanced about the use of technology in the music classroom, despite clearly being a app designer himself! He did recommend a few apps to us but emphasised that it’s hard to make a concrete long-lasting recommendation in such a fast-moving field. The few he cautiously recommended are here:

Elke Dommisch’s wonderful morning workshops playfully helped us to experience our piano-playing bodies in new ways, using the voice and movement to make us aware of how our body feels as we sit and play. These were a great deal of fun — I frequently found myself on the verge of laughter, I was enjoying myself so much. She also gave an insightful talk about stage fright that showed how our mental narratives can get in the way of us enjoying the thing we love.

Prof. Dr. Anne Fritzen gave a great talk about how students’ “dream pieces”, i.e. the pieces that they dream of playing. She interviewed many pianists, young and old, and shared some really valuable insights. Interestingly, not all students actually want to play their “dream piece”; they dream of being able to do it some day, but also know that it might be a massive commitment. I think her key message was that it is extremely valuable for piano teachers to talk to their students about their dream pieces, because we can learn a great deal from having these kinds of conversations — even if we don’t ever teach them the piece!

The pianist and improviser Michael Gees gave a talk and workshop on improvisation that re-emphasised a point that Ji-Youn Song had also made in her talk: when students are allowed to get creative with the music they are learning, when they are given permission to make interpretative and compositional changes to music, they gain a great deal of respect for other composers. This is the epitome of learning through play.

There was some exquisite playing from Prof. Klaus Oldemeyer, who encouraged us to playfully/seriously re-explore J.S. Bach’s Two-Part Inventions once more as adults. He admonished us with great humour not to use the pedal, but instead to pedal with our fingers (i.e. holding the keys of certain harmonies).

Yannis Bruckner gave a talk about the many ways students can playfully explore physical movement and technique at the piano. I confess that some of the German in this talk was hard for me to follow, partly because it dived into (I think) didactic theory and partly because I was very tired, but the musical examples and exercises he showed at the end were excellent: simple to do, obviously effective, and fun. Fans of Penelope Roskell’s excellent Essential Piano Technique books would thoroughly approve.

…and some English bloke called Garreth Brooke gave a talk about how to turn student mistakes into an opportunity to get creative, deepen their musical understanding, and help develop their sense of ownership. To my delight, this seemed to be very positively received and I was invited to deliver it again elsewhere, which was very cool. In the meantime I’ll look at whether I can turn it into a useful online resource, perhaps on this site.

The joy of togetherness

As I said in the video above, there’s something really special about coming together in person to exchange ideas. It’s powerful. I came away feeling invigorated and inspired.

Thank you very much to the Vorstand of EPTA Deutschland and to the staff of the Clara Schumann Musikschule in Düsseldorf for such a wonderful experience!

The next EPTA Deutschland conference will take place in Schwerin in the spring. See you there?